The history of Brower's Spring: The utmost source of the Missouri river in the Centennial mountains of Montana. Brower's spring is located approximately 200 miles upstream of Three Forks, Montana. As of 2023, there have only been 13 recorded descents from Brower's to the Gulf of Mexico- the longest water course in North America. Here is the story, including information on those who have descended the route.

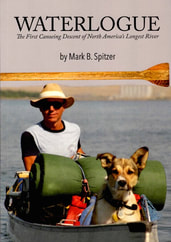

Update October 20, 2023. The account of the first known source to sea descent of the Missouri River system has been published this week! Waterlogue, written by Mark Spitzer, is of his historic solo descent from Brower's Spring to the Gulf of Mexico in 1989. Mark and his dog Groucho hiked and paddled the 3800 mile journey long before GPS, Internet, and Cell phones. The book is a must read, and contains over 50 color photos and 20 maps. You can order directly from Buffalo Commons Press by clicking LINK.

Mark is one of 13 known persons to have descended from Brower's Spring to the Gulf of Mexico. Read more about the others below.

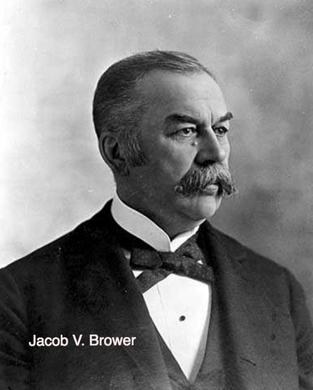

The Missouri river is formed by the joining of the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin rivers at Three Forks, Montana. These rivers where named in 1805 by the Lewis & Clark Expedition. This expedition proceeded up the Jefferson river to present day Clark Canyon reservoir where they stashed their canoes, obtained horses from the Lemhi Shoshone and proceeded up the westerly fork known as Lemhi Creek. After a couple days following this drainage, they arrived at what Lewis thought to be the "source of the mighty Missouri river", which they had toiled to reach over the past two years. This spring atop Lemhi pass is not the "utmost" source of the Missouri river. The "utmost" is defined by the longest water course a river makes. To the east of Lemhi creek and the left fork of the creek that the Lewis and Clark expedition veered from is the Red Rock river. This flows through the present day Centennial Valley to the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. Beyond these lakes to the south east, a creek flows out of the mountains off of the continental divide adding over 15-more miles to the watershed. This creek is know today as Hellroaring Creek, not to be confused with the creek of the same name to the east in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. The creek is founded by a tiny spring which originates from volcanic rock high in the mountains. This spring is known as Brower's Spring, after the man who discovered it on August 29, 1895, Jacob Vandenberg Brower. Brower was a Civil War veteran, surveyor and writer who also determined the utmost source of the Mississippi river at Lake Itasca in the 1890's and is known as the "Father of Lake Itasca".

Brower questioned Meriwether Lewis' claim of the true source and while studying maps claimed the source should be 100-miles east on Hell Roaring Creek near Mt. Jefferson. From Brower's Spring the water descends nearly 3800-miles to the Gulf of Mexico making it the longest river system in North America once combined with the Mississippi river. This is also the 4th longest river in the world. Survey records were basically lost or filed away until the Lewis and Clark Expedition Bicentennial was nearing in 2004, and people took interest in the true source.

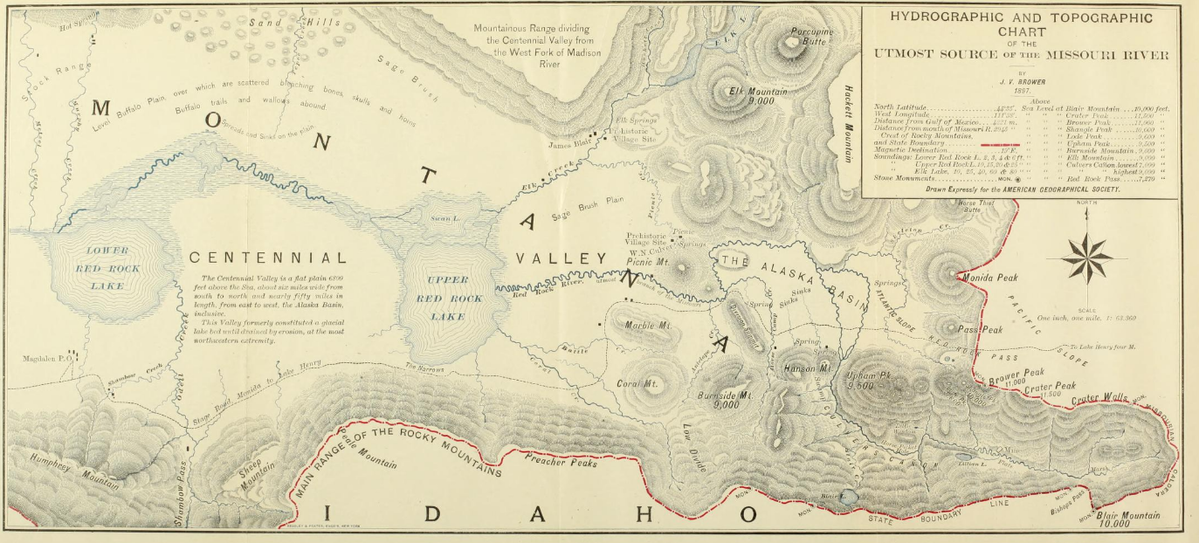

Below is the original 1897 topographic survey of the utmost source of the Missouri by Jacob V. Brower. The spring is located in the far right corner of the map above Blair Mountain.

Brower questioned Meriwether Lewis' claim of the true source and while studying maps claimed the source should be 100-miles east on Hell Roaring Creek near Mt. Jefferson. From Brower's Spring the water descends nearly 3800-miles to the Gulf of Mexico making it the longest river system in North America once combined with the Mississippi river. This is also the 4th longest river in the world. Survey records were basically lost or filed away until the Lewis and Clark Expedition Bicentennial was nearing in 2004, and people took interest in the true source.

Below is the original 1897 topographic survey of the utmost source of the Missouri by Jacob V. Brower. The spring is located in the far right corner of the map above Blair Mountain.

On August 29, 1895 , Brower and party including local rancher Culver arrived at what they determined to be the utmost source surrounded in a little basis with mountains. A year after the expedition a fire swept through the archives on December 19, 1896 of Brower's in Minnesota, destroying thousands of noets, maps, letters, and artifacts. His journal was published before the fire and if you are interested in reading Brower's entire Missouri River journal it can be found by clicking the link to the left:

A must read article is below in the Montana Outdoors magazine summer of 2005. The article explains the entire utmost source confusing and is a must read . The article is co-authored by Tony Demetriades who owns the property at the base of Hell Roaring Creek which you have to cross over to exit the canyon. Tony has been very helpful in allowing paddlers to hike and even camp on his land during their journey to Brower's Spring. (Click Link below-left to read)

A must read article is below in the Montana Outdoors magazine summer of 2005. The article explains the entire utmost source confusing and is a must read . The article is co-authored by Tony Demetriades who owns the property at the base of Hell Roaring Creek which you have to cross over to exit the canyon. Tony has been very helpful in allowing paddlers to hike and even camp on his land during their journey to Brower's Spring. (Click Link below-left to read)

Descents: Source to Sea

The history of paddlers descending North America's longest rivers system is a fairly new concept. The "Source to Sea" trend starting with the race to descend the Amazon from its source to the sea in the early 2000's, which carried over to a few intrepid paddlers wanting to descend the Missouri river and other rivers on the other continents. As of this writing (November-2023), there have been only 13 known people to descend the 4th longest river in the world from its source at Brower's Spring. There have only been 12-people that has walked on the moon, so the Brower's group is a very elite group of men and woman. Coincidently, all are members of the Missouri River Paddler Org (MoRP). (Recent research discovered on February 28, 2019, found that a Geoff Conklin started at the source in 1974 attempting to paddle to the Gulf, but ended his journey at Ft. Yates, ND. Conklin paddled from the culvert and road crossing on Hellroaring creek, to the Red Rock Lakes, and the Red Rock River, which much of this was portaged by those who followed years later, including the upper lakes which are closed today due to nesting birds.) A recent December 2019 discovery changed the entire records. It was discovered that Mark Spitzer had made a solo canoe descent starting at Brower's Spring and going to the Gulf in 1989-90! The records below reflect this new discovery.

The man who gets the title as the "Grandfather" of the Brower's group is Texan Andy Bugh who did extensive research and recon in the Hell Roaring creek canyon which other paddlers would use over the next years to reach the source. Andy didn't quite reach the spring, but started his descent to the Gulf of Mexico from Lima, Montana on the Lower Red Rock River in 2011. (Image: Andy Bugh)

Below is a list in chronological order of the Brower's Spring paddlers who made history by starting at the utmost source and descending North America's longest watershed to the Gulf of Mexico--3800 miles

(First known attempt was by Geoff Conklin in 1974, see above)

As of December-2019 the known descents are as follows:

1: North Dakotan Mark Spitzer: 1st known descent: June 13, 1989 to January 1990. Mark was recently discovered to have beat the previous record by 23-years, that of Mark Kalch. It took Spitzer 7 months and 1-day to reach the Gulf. He hiked and walked all portage routes around the dams and paddled a Wenonah Spirit canoe partnered with his dog Groucho. (Mark finally published the account of this journey in October of 2023. See above to purchase Mark's book Waterlogue.

2: Australian Mark Kalch: 2st Descent- June 10-2012 ( First descent by "kayak", 117-days) Kalch was thought to be the first known person to descend the Red Rock River and proceed to the Gulf until the discovery of Spitzer's records above. Mark has to-date paddled the longest rivers on 4 continents from their source to the see. The only person to do so. (Amazon, Missouri, Volga, Murray-Darling) Kalch paddled a P&H Sea Kayak.

3: Canadian Rod Wellington. 1st Canadian descent. (Wellington descended the Red Rock River by Pack Raft and also paddled the Upper Red Rock Lakes. Rod probably paddled more miles than the others because of this.

4: Janet Moreland: This Missourian became the 1st woman! A total of 123-days. EddyLine Shasta Kayak. Janet has gone on to paddle the Mississippi and Yukon Rivers solo from source to sea.

5: Paul Gamache: (California) Speed record and most complete paddle descent as Paul was able to kayak a large portion of Hell Roaring creek in a whitewater play boat, whereas most walk down the canyon from the spring. Paul arrived at the Gulf of Mexico 77-days after departing Brower's Spring.

6/7: Nick Caiazza & Joe Zimmerman (Colorado) 1st decent by "Sit on Top" Kayaks and 1st duo expedition. Hobie Sit On Top Kayaks. Nick produced an award-winning documentary film on their descent.

8: Dale Waldo (Michigan) Dale descended to St. Louis in a record 55-days. Dale ended this trip in St. Louis. However, the previous year he paddled the entire Mississippi to the Gulf. Dale has the miles and route completed, just not as one-push to the sea. Wenonah Canoe

9: Allen Palmer (Oregon) Read Allen's Detailed account into Brower's Spring: Click Here

~At the bottom of the page is an in depth trip report by Allen from Brower's to Three Forks.

10: Kris Laurie (New York) 2nd complete descent by a Canoe. RoyalEx Mad River Explorer

11/12: Lisa Pugh & Alyce Kuenzli (Minnesota) 1st women team by canoe and most complete descent by woman, having portaged under their own power. (No rides around dams etc)

13: Dirk Rohrbach (Germany) Home made stripper kayak. Dirk reached the Gulf after 125 days since his start at Brower's Spring. (1st Source to Sea Decent by a German) Dirk published the 1st book on this subject matter of source to sea, which is written in German and entitled, "IM FLUSS", which can be ordered here: BOOK

There is extreme difficulty and logistical challenges associated with making a decent from Brower's Spring, which is the reason for its unpopularity. You need to reach the Gulf of Mexico before hurricane season, which puts your start date at the end of May or first part of June. The Centennial mountains can still be buried under 2-10 feet of snow as was the case for most of the above paddlers. Skis and snowshoes are a must in reaching the spring. The closest road access is the US Forest Service Road to the east of the spring which goes to Sawtelle Peak. The road is not open to traffic until around the end of May. If you plan an earlier start, you will need to seek permission to access the gated/locked road. If you ascend from the Red Rock valley to the spring, you most likely will need more than one day due to the extreme elevations, snow, high avalanche danger and the threat by grizzly bears which are coming out of hibernation with cubs about this time. Just read the reports of those who did it before to get a sense of the challenges.

The actual location of the spring can be difficult to see in the early spring with 10-feet of snow covering it. This can be a let down if you expected a free flowing spring. It really depends on the winter snow accumulations on wether the spring will be melted out. There is a large rock cairn near the spring which contains a log book register inside of an old army ammo can. Make sure you sign in and read the other names there. The register fills up each summer as it is a popular place to obtain drinking water for those hiking the Continental Divide Trail (CDT) from Canada to Mexico.

Navigation down canyon can be extremely challenging. Downfall, thick forest, steep ridges, narrow deep canyons are just a part of the 8-miles from the spring to the valley floor. You may be thinking, "8 miles?, that's not that far, I can walk that in 4 hours". Think again! This author skied into the spring with Janet Moreland when she made her historic descent in 2013. We had anticipated to do the 8 mile ski in about 5 hours. It took us 31-hours! Since we anticipated a quick descent, we avoided taking tents, sleeping bags, matches, stove, extra food water and clothing. It could have been life threatening but we survived by making a bivy shelter out of pine boughs and hunkering down in the 10F temperatures that night with no fire or sleeping bags. I would allow for a two day trip from the spring out to the road, to play it safe. Speed paddler Paul Gamache was able to descend part of Hell Roaring Creek in his white water play boat which he carried in with from the Sawtelle Road. Paul found it difficult with frequent downed trees over the creek which caused him to stop, exit kayak, portage around, and then get back in. The best source of information is to contact all the paddlers above and pick their brains with questions as to what to expect and to read the available information.

Once you reach the valley floor you will be rewarded with the fact you made it to the source of the longest river in the country as well as having wonderful views of the Centennial Valley. As you exit onto the valley, you will encounter barbed wire fences that you will have to cross. This is Private Property. The land owner is Tony Demetreadis from Bozeman, Montana. Tony, has been helpful to paddlers and has allowed them to cross over his land and even make camp down by the creek as in the case with Mark Kalch. (Contact us for Tony's contact info). From the valley to the Upper Red Rock lake is a braided willow choked narrow swift water stream that is difficult to exit due to the vegetation and fast water. Rod Wellington was able to make it through with a pack raft. Be aware of angry cow moose with their young when you surprise them coming around a bend.

Once you reach Upper Red Rock Lake you are in a predicament. The lake is OFF LIMITS and closed most of the spring and summer due to rare nesting birds. You must portage...i.e walk the road about 20 miles to Lower Red Rock Lake.

The fun has only begun...pun intended. The next 70+ miles have been described as the "worst paddling I've ever seen", by Mark Kalch. There are over 50 barbed wire fences that cross the river! Not only are there barbed wire fences, but many are electric! The Lower Red Rock River can be very fast flowing in the spring with no exit points due to think stands of alder and willow right up to the bank and overhanging a ways into the river. Just imagine coming around a bend and there is a fence across the river. No time to eddy out! You will have to jump out of your boat in chest deep icy water before being pushed through the fence. Of the 12 Source to Sea paddlers in the above list, only 4 have made the descent by boat. The other 8 portaged around to Clark Canyon Reservoir.

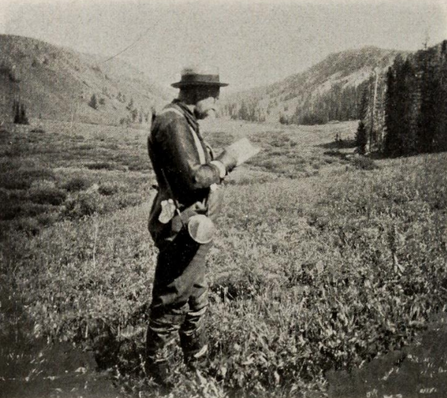

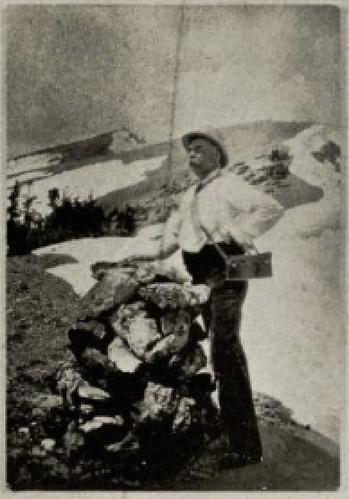

Photos Below: (R) Jacob Brower on August 29, 1895 making notes of Culver Canyon which today is called, Hell Roaring Canyon. I believe this photo is just upstream of Lillian Lake. The photo below (L) is from Allen Palmer.

I believe this is the same approximate location, or at least the direction. I think the image of Brower was a little more further down canyon a hundred yards. (Note the tall dead tree in front of Brower and to the right center of image could be the same dead tree in the image below to the right edge.) Amazing to see Brower on the day he discovered the utmost source...118 years before the bottom photo was taken.

I believe this is the same approximate location, or at least the direction. I think the image of Brower was a little more further down canyon a hundred yards. (Note the tall dead tree in front of Brower and to the right center of image could be the same dead tree in the image below to the right edge.) Amazing to see Brower on the day he discovered the utmost source...118 years before the bottom photo was taken.

Photos above from same approximate Location. Brower's on Right in 1895

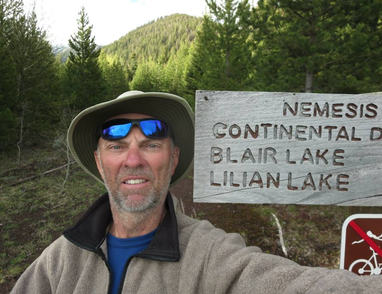

If you descend into Brower's Spring from the Forest Service road near Sawtelle Peak, you will be following the Continental Divide Trail (CDT). If the snow has melted, it is a well marked trail which brings you along the ridge as seen in the historic photo of Jacob Brower (Left) and the images below. It takes approximately 1-2 hours to reach Brower's Spring. This depends on depth of snow, weather, and your physical condition. You are at a high elevation and the air is thin!

(Left) Jacob V. Brower at a rock cairn built in 1895 with Jefferson Peak in the back ground. This location is on the ridge above the spring when you descend from Sawtelle Peak. Jefferson Peak was once named Brower Peak.

I believe the photo to the right and below, is the identical place of Jacob V. Brower's photo above. There are some rocks at the bottom left corner of the photo below that may be the remains of the rock cairn. You can also see the rock behind Brower's lower leg calf that I believe to be the same rock in the center of the photo below. Photo (Right) of Janet Moreland approaching the same location as the Brower's 1895 image above.

Below are historic photos and a slideshow from Jacob Brower's expedition to survey the source of the Missouri river in 1895. A few of the images are of William and Lillian Culver who traveled with Brower to reach the spring. Lake Lillian was named after her. Amazing to see the same area that many of our paddlers have hiked to reach. A lot has changed in 100-years, but you can still see recognizable features.

Click arrow below to start the slide show.

Click arrow below to start the slide show.

Rod Wellington photo

2012

Rod Wellington photo

2012

(L) Photo by Rod Wellington at the utmost source of the Missouri river--Brower's Spring. Rod takes a little water sample for his descent.

(R) Paul Gamache after descending Hell Roaring Creek from below the actual spring. Plenty of downed trees and portaging for Paul during his descent from the spring.

Paul descended by kayak,

the closest to the actual spring than anyone.

Paul would arrive at the Gulf of Mexico in 77-days!

Below are a series of photos from Brower's Spring taken by the author

as well as many of the MoRP members during their descent.

Click to enlarge or hover over for more details.

as well as many of the MoRP members during their descent.

Click to enlarge or hover over for more details.

Below is a series of photos from Brower's Spring to the Centennial Valley.

The descent along Hell Roaring Creek is very challenging. The 8 mile descent can take 2-days!

The images will give you an idea of the terrain, the size of the creek and the challenges you will face.

Photos by Dale and Rick Waldo, Allen Palmer, Jacob Brower, Rod Wellington, and Norm Miller

The descent along Hell Roaring Creek is very challenging. The 8 mile descent can take 2-days!

The images will give you an idea of the terrain, the size of the creek and the challenges you will face.

Photos by Dale and Rick Waldo, Allen Palmer, Jacob Brower, Rod Wellington, and Norm Miller

BELOW: (L) Lillian Lake taken by Brower's Expedition in 1895 compared to approximate location (R), taken by Rod Wellington in 2013.

Note the dead fallen tree in the foreground, may possibly be the same tree in the right photo, bottom left corner under surface.

Note the dead fallen tree in the foreground, may possibly be the same tree in the right photo, bottom left corner under surface.

The photos below are from the base of Hell Roaring Creek where it enters the Centennial Valley. Most likely you will portage 20-miles to the Lower Red Rock River before you begin paddling. The road is a well-maintained dirt road, so you could also cycle as an option.

Many of the photos below are the section between the Lower Red Rock Dam & Clark Canyon Reservoir.

Click images to enlarge.

Thanks to Allen Palmer, Dale Waldo, Rod Wellington, and Nick Caiazza.

A detailed trip report written by Allen Palmer is below towards the bottom of the page.

Many of the photos below are the section between the Lower Red Rock Dam & Clark Canyon Reservoir.

Click images to enlarge.

Thanks to Allen Palmer, Dale Waldo, Rod Wellington, and Nick Caiazza.

A detailed trip report written by Allen Palmer is below towards the bottom of the page.

(Left- Video of death trap on the Red Rock River. Click Image to play )

Once you are paddling on the Red Rock River, you will encounter over 50-fences across your path as well as many low-head bridges which you cannot get under and must portage. Here is a video taken by Dale Waldo showing one of the fences across the river. Imagine trying to slow down as you approach this life-threatening situation.

Below are a series of photos showing a few of the obstacles on the Red Rock River, mainly the fences which cross over. The situation may be more dangerous in higher water levels. Some of the fences are ELECTRIC!

Once you are paddling on the Red Rock River, you will encounter over 50-fences across your path as well as many low-head bridges which you cannot get under and must portage. Here is a video taken by Dale Waldo showing one of the fences across the river. Imagine trying to slow down as you approach this life-threatening situation.

Below are a series of photos showing a few of the obstacles on the Red Rock River, mainly the fences which cross over. The situation may be more dangerous in higher water levels. Some of the fences are ELECTRIC!

Downstream of Lima to Dillon, Montana, you will encounter more fences until you reach Clark Canyon Reservoir. From there, the river will open up, be swifter but still challenging.

Below are images from that section of the river.

Thanks to Allen Palmer and Dale Waldo.

Below are images from that section of the river.

Thanks to Allen Palmer and Dale Waldo.

(L) Allen Palmer in search of Brower's Spring- The ultimate source.

The most in-depth trip report regarding getting to Brower's Spring and descending the watershed all the way to Three Forks is written up by Allen Palmer during his 2015 decent. This report shows you the logistical challenges of this route. If you are planning a decent down Hell Roaring Creek, Red Rock Lakes, the Red Rock River, Beaverhead River and the Jefferson Rivers to the headwaters of the Missouri, this report is a must-read!

CLICK the BUTTON BELOW and print for your records!

Skiing to the Ultimate Source of the Missouri river-Brower's Spring

Written April 28, 2013, by Norm Miller after skiing to Brower's Spring with Janet Moreland during her expedition.

Miller & Moreland had anticipated an 8-hour ski decent, but it turned into 31-hours!

Read the harrowing account below:

I angled the lens of the binoculars, so the sun's light concentrated on the piece of toilet paper and pine needles placed neatly in the snow. Focusing the beam for several minutes produced no smoke, not even a discoloration in the paper. It looked as though there would be no fire for Janet and I this evening!

A few days earlier I made reference to a quote by Polish philosopher Alfred Korzybski; "The map is not the territory" on the Mo Paddler Facebook Page. Ironically, I failed to adhere to the lessons or message. In short, the meaning of this quote is: "Our perception of the world is being generated by our brain and can be considered as a 'map' of reality written in neural patterns. Reality exists outside our mind, but we can construct models of this 'territory' based on what we glimpse through our senses."

Boy did I screw up!!! The reality is that no map tells you what is ON the ground or what you will or might experience. Many variables are encountered. A map does not show 6-15 feet of snow, thick forested ridges and ravines, avalanche bowls and cornices, and things like--what would happen if we had to bivy and spend the night out?

Another huge factor was most all of the information we obtained was from people who had been to Browers Spring in the summer or late spring when there was NO avalanche danger, and one could walk anywhere. More of a straight line without having to negotiate hazards and obstacles. I knew all this before, having back country skied, taught telemark skiing, and mountaineered for years while living in the Tetons of Wyoming.

Curt Judy from the Idaho Dept. of Transportation (I think this is the title), assisted by opening the US Forest Service gate near the bottom of Sawtelle Peak so we were able to drive within an short distance to the upper spring in which we would ski to. This saved us hours of uphill travel. From there we followed the drainage--Hellroaring Creek northwest towards the Red Rock River.

There were no clouds in the sky as we departed our support crew of Haley and Jeanie from high up in the mountains. We traversed to the ridge gaining a few hundred feet in elevation. We followed the ridge line near Jefferson peak which was spectacular.... the drop off to the north fell well over 1000' feet! As we reached the drainage of the upper source of the Missouri, I had no feeling of being on a "river-trip". This was a total back country ski journey. The upper bowl comprises of about 350-acres and was covered in 6-15 feet of snow. Janet and I worked out the cobwebs in our skiing, making figure 8's in the snow. We attempted to dial in on the exact spot by relying on memories of photos that others had taken before us. It looked so different. There was no gully where the spring trickled out of the rock...it was drifted and filled with deep snow. It would have taken a day just to dig down to the water with our shovels. Janet zeroed in on the "spot" with her GPS, and I informed her that ALL the snow you see in every direction IS the source! It will all melt and become water and drain into the creek eventually reaching the Gulf of Mexico.

We both were using modern telemark skis, plastic telemark boots and bindings, we each carried an avalanche shovel and a set of probe poles in case we had to dig each other out of an avalanche. And most importantly we each had avalanche transceivers which are an electronic device that sends out a signal to the other persons device which allows them to precisely locate where a person is buried...thus the place where you would start to dig. Typically, those caught in avalanches have only about 4-minutes of air before they would die. I have had three friends killed in avalanches and know others who have been caught in them. Janet had once worked as a member of the US Ski Patrol at a ski resort in California and knew of the risk and dangers as well. We both were cautious in choosing our route down and across open bowls. Typically, a wind loaded slope of more than 33` degrees has the potential to slide. Also, the conditions of the snow, the temperature of the snow and the type of snow layers plays a huge factor. The worst conditions are old snow on the bottom layers that are cold and have the consistency of sugar with a heavy wet layer on top. This snowpack is dangerous and is typically what people are killed in. The heavy wet layer does not attach to the layer below, add steepness and it gives way and slides. It's sort of like placing a heavy book on top of a table covered in sugar granules, once the book is placed, lift one end of the table higher than 33` degrees. The sugar will act like tiny ball-bearings causing the book to slide. The more snow on top of such a weak layer the larger the avalanche field of debris. My friends in Colorado that died in the late 80's in an avalanche were buried under 50-ft of snow and the debris field was over a 1/2 mile wide!

Since we were focused on our safety there was not a lot of jubilation in reaching the "source", at least from my point of view. I think Janet was feeling it more inside as this was her true "starting" point. Everything was all downhill so to speak. I knew that every snowflake would melt and eventually drain out and become the Missouri River. The previous year Mark Kalch reached this point too, having snowshoed up the canyon to the source and back down to camp in about 10-hours. I tried to compare from memory his photos of the source to what we were seeing. The gully where the water trickles out was totally filled in with deep snow.

From this point we made fairly good time working our way downstream. We stayed higher up in the bowls and cut turns along treed ridge lines. About 1/2 a mile below the source, the creek was free flowing, unfrozen and about 3 feet wide. We were unable to touch the water or even get close as the snow depth next to the creek was 6-9 feet. If we got too close the edge may break off sending us into the water and no way to get out. The canyon began to get narrower too. The north side became one giant potential avalanche field, so we knew not to cut a ski track across any part of the slope.

We found a small snow bridge over Hellroaring Creek and crossed over to the south. From here we had to climb a few hundred feet up to the ridge, so we put our climbing skins back on our skis. Climbing skins are basically fabric that is attached on the bottom of your skis via a sticky glue from tip to tail. The skins are connected to the tips and tail of each ski. When you need to go up a hill the skins provide resistance--keeping the ski from sliding backwards...allowing you to go up and forward. When you reach your high point and want to ski down, you just pull the skins off your skis and fold them up and put away.

The views from the ridge were spectacular! To the SW we could see the Sawtooth Mountain range near Sun Valley Idaho...a distance of over a 100-miles. To the north side of the creek, Mt. Jefferson and Mt. Nemesis covered a 25,000-acre expanse and one giant potential avalanche! We skied and worked our way up and down and through thick stands of timber. We were not sure exactly the route we needed to take because at times we could not even see the creek or the drainage below. Our focus was to constantly pick the safest route and to be moving forward.

We both were excited and felt we were nearing the 1/2-way point. Our slow but steady progress at times was physically demanding. Often we would drop down 300-ft closer to the creek in hopes of getting near the bottom on the so-called flat ground, only to find that the slope became too steep, forming a small canyon or ravine. This meant we had to turn around and climb back up and try to find a ridge or gentler slope to cross over. At times our pace was only 1/8th of a mile per hour.... our fastest was nearly a 1/4 mph! We both were carrying 25-lb backpacks. On our feet were heavy telemark ski boots and skis. My size 13 boots and skis probably weigh nearly 20 -lbs each leg....so having to climb back out of a ravine and lifting my leg with such weight over and over and over again became very exhausting.

We made it to the area just above Lily Lake. The entire lake and flat marshy area surrounding the lake was covered with deep snow. It provided some relief by traveling along flat level ground for an hour. Beyond the lake (which we both could not even tell was a lake since it looked like a snow-covered field) we made the error of dropping too steeply into the canyon. Janet wiped out in a soft patch of snow landing on her face and jamming her sunglasses into her forehead. I heard her yell out and turned and went over to her. Blood was covering her forehead. A large rug burn type gash covered a large part of her head! She spent a few minutes stopping the bleeding with a tissue. We both drank water and had a bite of food. I think at this point we realized there was no way in hell we were going to get out before the sun went down.

In a small opening in the ridge, I turned on my walkie-talkie radio and was surprised to reach Janet's daughter who was at the car at our exit point. This was good, because had we not been able to tell her our situation she may have been worried for our safety. I assured her we were tired but ok, would make camp and try and call again in the morning when we departed. We headed back towards the lake and agreed that we severely needed more drinking water. We spent an hour going back up the canyon across the flats to a small area where Hellroaring creek snakes its way through the snow-covered field. Since the snow was too high along the edge, we could not reach down to fill our water containers. I devised a plan to unfold my avalanche probe pole which is 10-feet long and hook my water bottle on the end of the probe. I could then use this to lower the bottle to the water and scoop out water and refill all our water containers. We were both somewhat dehydrated at this point and each drank nearly a quart of water each. We didn't have a water filter with us and agreed that we didn't care. We thus drank directly from the upper source of the longest water system in North America!

Once hydrated we headed back across the open field toward the lake. Janet suggested the large group of trees on the upper end of the lake as a place to spend the night. We didn't carry a tent or heavy sleeping bags. We knew it would be a very uncomfortable cold night with very little sleep if any. The only thing that made us a little uncomfortable was the fact that neither of us had any matches or a lighter to start a fire! What the FUCK were we thinking! In the years of back country skiing and hiking I've always had fire starter. Not this time. Something got lax along the way, I got lazy in believing we would be out in 6-hours!!!! WRONG!!!! This was a good realty checkpoint for both of us, sort of a wakeup call to pay attention to "the moment", realizing the map was NOT the territory. We could have been in worse shape. We both had extra clothing and hats to wear, I carried a small bivy sack I could climb into for extra warmth. Janet's entire feet and lower half of her legs would slide into fit entirely into her backpack.

I attempted to make a fire using the lens from my binoculars and focusing the sun's beam onto some paper and sticks. No luck! A shelter was quickly constructed. Janet used her shovel to dig an area out of the snow like two side by side recliner chairs. I placed our probe poles and ski poles over the top to create the framework for a roof. I then gathered pine tree limbs and bows and covered the sides, top and bottom of our shelter to help protect us from the cold.

Prior to departing that morning, Janet's daughter gave me a 24-oz. can of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer as sort of a "victory at the source" beverage. We were determined we needed the fluid, and the 240 calories of carbohydrates it provided. And I sure as hell was not going to carry it out the next day. So once we finished with our shelter, I popped open the can and we passed it around until it was gone. Probably not the best beer I've ever had since the air temps were already dropping into the teens and the beer too was almost too cold to drink.

Since I or we (no blame here...we are all responsible for ourselves...we just made a few errors in judgement with our time) had eaten what food we had during the day we went to sleep deprived of a big meal. I in fact ended the evening with my final item of food for the entire trip .... a Hershey chocolate bar!

Janet nor I were concerned or worried about any danger in all reality. In fact, we were in great sprints-- having just rehydrated on a lot of water, built a shelter, talked to Haley on the radio, drank a beer, put on all our warmer cloths, ate a bite of food, and not having to ski no more for the rest of the day! We figured the temps would drop into the teens. Not a cloud in the sky as the sun disappeared in the west.... the twilight blue of the snow darkened only slightly....by 9pm the giant moon popped over the ridge shining down onto our home for the night. The moons light was so bright that we could see miles back up canyon.

With all our cloths on we tossed and rolled around all night. Janet was probably the coldest however I didn't know this until the next morning when she told me how cold she had gotten. We passed the entire night without speaking, only concentrating on our discomforts. I actually drifted off to sleep maybe 10-minutes the entire night. Still wearing my heavy large ski boots I tried to wiggle my body into the pine boughs and sides of snow shelter...nothing was comfortable. I could hear Janet every few minutes trying to reposition herself with her own discomfort. The moon arced across the sky all night and by around 6am the faint light of a new day was starting to form.

We most likely would have gotten several hours of sleep had we had a fire. Upon awaking, Janet exclaimed "that was the worst night of my life!"...I think I second that! We packed our gear in near silence, trying to warm up and fully awaken from miserable night. We departed our shelter about 730am....we had only about 4 1/2 miles to go! Little did we know that it would take another 8 1/2 hours to reach the end.

We began our climb up into the trees gaining a high point on the ridge. We both could see the rock canyon at the exit of Hellroaring Creek...yet hours away. An hour or so later we found the small wooden sign marking the CDT-Continental Divide Trail which goes from Mexico to Canada! We celebrated this small confidence and moral booster. We tried to follow the trail but since the ground is snow covered, it was impossible. Again, we dropped too low and had to climb back up. Constantly losing elevation only having to climb back up which we painstakingly had just descended.

I was having challenges dealing with the demons in my mind telling me we would not make it out of here for another night. I was determined to beat this devil away and not become the subject of another John Krakauer book about ill-prepared wilderness travelers dying in the back country.

Our exhausting and frustrations would occasionally well up to the surface between us and pour out as outburst, a few terse words or sighs of disbelief in having to climb back up 300-feet where we already were. We both knew we could not spend another night out in the cold.

We both commented on the descriptions of past travelers and how their journey was nothing like what we were experiencing. Even the description of people who ski this area regularly seemed far from reality.

Probably the best decision we made on this day was to take off our skis and walk in our boots! We attached the skis to the outside of our packs and walked through the snow. This allowed for quicker travel since we no longer had to work our long skis through the tight and confined forest trees. We were able to walk more in a straight line. Since the nights had been cold the snow stayed firm. We rarely broke through more than an inch or two until later in the day when the snow softened a little more. We could see the "knob" at the end which we had to skirt around getting closer and closer. Occasionally we would see old ski tracks in the woods and would follow them until they disappeared. This boosted our confidence knowing that other people had been coming in this far for a day of skiing. We dropped to the level of the creek. It was wide and open in some areas, whereas other areas the sides dropped too steeply into the creek. Along the bottom I noticed a set of grizzly bear tracks. They looked a few days old but provided something else to be aware of. We were both carrying bear-spray...which is a pressurized canister of capsaicin-- sort of like a mini fire extinguisher. Capsaicin is made from chili peppers and when sprayed at a bear it causes temporary blindness and respiratory trauma. There has never been a human casualty from a grizzly bear attack from using bear spray!

I knew we had the potential to encounter a bear since it is spring and they have been coming out of hibernation now for a month. Later we saw a fresher set of tracks probably a day old. We began to make more noise as to spook the bear. Grizzly have a fear of man too and they prefer not to be anywhere near a human. Most all bear attacks are from people who are too quiet and end up surprising a mother bear and her cubs. Thus I hollered, whistled, and made loud noises as we proceeded though the woods. The closer to the outlet of the canyon our adrenaline was high. We were certain we would be out soon. I occasionally was able to reach Janet's daughter on the radio. The conversation was broken by the weak signal but I was able to say we are making "progress".

We soon had dropped enough in elevation that we encountered patches of dirt and open rocky scree fields which we traversed. Near the canyon bottom we tried to find the so-called bridge but it must have been under 5 feet of snow still. Exhausted, hungry and mentally drained we stopped to rest and drink more of the river water we collected the day before. The sun was shinning bright, temperatures were probably in the high 50's, and the snow was getting soft and mushy. The crux of our journey would be one final 400 ft. climb up thought a notch to the left of the canyon. Slow and steady.....one foot in front of the other. We picked a route that was more open so as the skis on our packs would not get hung up on hanging tree limbs. I was still hollering out at mama bear...as to give her a little warning as to our presence. At the very top of the notch was the freshest grizzly bear tracks we had seen. The bear was most likely there just 5-minutes before!! We could tell that the bear had heard me making noise since the tracks made a 90-degree right turn away from us at that particular point! We could see the claw marks and the perfect outline in the melting snow.

A quick 20-minute drop down through trees led us to the valley floor where we had clear contact by radio with our support crew and the vehicles!

We made it to Browers Spring and out! What we thought would take a total of about 6 hours took us 31 hours! I was impressed with Janet's determination and constant forward progress when I knew she was totally spent. There were times I knew she would cringe when I said that we had to climb back up and over another ridge. One step and time, one stroke at a time will get you to the ocean!

Go Janet Go!

Norm Miller

Livingston, Montana

April 28, 2013

Written April 28, 2013, by Norm Miller after skiing to Brower's Spring with Janet Moreland during her expedition.

Miller & Moreland had anticipated an 8-hour ski decent, but it turned into 31-hours!

Read the harrowing account below:

I angled the lens of the binoculars, so the sun's light concentrated on the piece of toilet paper and pine needles placed neatly in the snow. Focusing the beam for several minutes produced no smoke, not even a discoloration in the paper. It looked as though there would be no fire for Janet and I this evening!

A few days earlier I made reference to a quote by Polish philosopher Alfred Korzybski; "The map is not the territory" on the Mo Paddler Facebook Page. Ironically, I failed to adhere to the lessons or message. In short, the meaning of this quote is: "Our perception of the world is being generated by our brain and can be considered as a 'map' of reality written in neural patterns. Reality exists outside our mind, but we can construct models of this 'territory' based on what we glimpse through our senses."

Boy did I screw up!!! The reality is that no map tells you what is ON the ground or what you will or might experience. Many variables are encountered. A map does not show 6-15 feet of snow, thick forested ridges and ravines, avalanche bowls and cornices, and things like--what would happen if we had to bivy and spend the night out?

Another huge factor was most all of the information we obtained was from people who had been to Browers Spring in the summer or late spring when there was NO avalanche danger, and one could walk anywhere. More of a straight line without having to negotiate hazards and obstacles. I knew all this before, having back country skied, taught telemark skiing, and mountaineered for years while living in the Tetons of Wyoming.

Curt Judy from the Idaho Dept. of Transportation (I think this is the title), assisted by opening the US Forest Service gate near the bottom of Sawtelle Peak so we were able to drive within an short distance to the upper spring in which we would ski to. This saved us hours of uphill travel. From there we followed the drainage--Hellroaring Creek northwest towards the Red Rock River.

There were no clouds in the sky as we departed our support crew of Haley and Jeanie from high up in the mountains. We traversed to the ridge gaining a few hundred feet in elevation. We followed the ridge line near Jefferson peak which was spectacular.... the drop off to the north fell well over 1000' feet! As we reached the drainage of the upper source of the Missouri, I had no feeling of being on a "river-trip". This was a total back country ski journey. The upper bowl comprises of about 350-acres and was covered in 6-15 feet of snow. Janet and I worked out the cobwebs in our skiing, making figure 8's in the snow. We attempted to dial in on the exact spot by relying on memories of photos that others had taken before us. It looked so different. There was no gully where the spring trickled out of the rock...it was drifted and filled with deep snow. It would have taken a day just to dig down to the water with our shovels. Janet zeroed in on the "spot" with her GPS, and I informed her that ALL the snow you see in every direction IS the source! It will all melt and become water and drain into the creek eventually reaching the Gulf of Mexico.

We both were using modern telemark skis, plastic telemark boots and bindings, we each carried an avalanche shovel and a set of probe poles in case we had to dig each other out of an avalanche. And most importantly we each had avalanche transceivers which are an electronic device that sends out a signal to the other persons device which allows them to precisely locate where a person is buried...thus the place where you would start to dig. Typically, those caught in avalanches have only about 4-minutes of air before they would die. I have had three friends killed in avalanches and know others who have been caught in them. Janet had once worked as a member of the US Ski Patrol at a ski resort in California and knew of the risk and dangers as well. We both were cautious in choosing our route down and across open bowls. Typically, a wind loaded slope of more than 33` degrees has the potential to slide. Also, the conditions of the snow, the temperature of the snow and the type of snow layers plays a huge factor. The worst conditions are old snow on the bottom layers that are cold and have the consistency of sugar with a heavy wet layer on top. This snowpack is dangerous and is typically what people are killed in. The heavy wet layer does not attach to the layer below, add steepness and it gives way and slides. It's sort of like placing a heavy book on top of a table covered in sugar granules, once the book is placed, lift one end of the table higher than 33` degrees. The sugar will act like tiny ball-bearings causing the book to slide. The more snow on top of such a weak layer the larger the avalanche field of debris. My friends in Colorado that died in the late 80's in an avalanche were buried under 50-ft of snow and the debris field was over a 1/2 mile wide!

Since we were focused on our safety there was not a lot of jubilation in reaching the "source", at least from my point of view. I think Janet was feeling it more inside as this was her true "starting" point. Everything was all downhill so to speak. I knew that every snowflake would melt and eventually drain out and become the Missouri River. The previous year Mark Kalch reached this point too, having snowshoed up the canyon to the source and back down to camp in about 10-hours. I tried to compare from memory his photos of the source to what we were seeing. The gully where the water trickles out was totally filled in with deep snow.

From this point we made fairly good time working our way downstream. We stayed higher up in the bowls and cut turns along treed ridge lines. About 1/2 a mile below the source, the creek was free flowing, unfrozen and about 3 feet wide. We were unable to touch the water or even get close as the snow depth next to the creek was 6-9 feet. If we got too close the edge may break off sending us into the water and no way to get out. The canyon began to get narrower too. The north side became one giant potential avalanche field, so we knew not to cut a ski track across any part of the slope.

We found a small snow bridge over Hellroaring Creek and crossed over to the south. From here we had to climb a few hundred feet up to the ridge, so we put our climbing skins back on our skis. Climbing skins are basically fabric that is attached on the bottom of your skis via a sticky glue from tip to tail. The skins are connected to the tips and tail of each ski. When you need to go up a hill the skins provide resistance--keeping the ski from sliding backwards...allowing you to go up and forward. When you reach your high point and want to ski down, you just pull the skins off your skis and fold them up and put away.

The views from the ridge were spectacular! To the SW we could see the Sawtooth Mountain range near Sun Valley Idaho...a distance of over a 100-miles. To the north side of the creek, Mt. Jefferson and Mt. Nemesis covered a 25,000-acre expanse and one giant potential avalanche! We skied and worked our way up and down and through thick stands of timber. We were not sure exactly the route we needed to take because at times we could not even see the creek or the drainage below. Our focus was to constantly pick the safest route and to be moving forward.

We both were excited and felt we were nearing the 1/2-way point. Our slow but steady progress at times was physically demanding. Often we would drop down 300-ft closer to the creek in hopes of getting near the bottom on the so-called flat ground, only to find that the slope became too steep, forming a small canyon or ravine. This meant we had to turn around and climb back up and try to find a ridge or gentler slope to cross over. At times our pace was only 1/8th of a mile per hour.... our fastest was nearly a 1/4 mph! We both were carrying 25-lb backpacks. On our feet were heavy telemark ski boots and skis. My size 13 boots and skis probably weigh nearly 20 -lbs each leg....so having to climb back out of a ravine and lifting my leg with such weight over and over and over again became very exhausting.

We made it to the area just above Lily Lake. The entire lake and flat marshy area surrounding the lake was covered with deep snow. It provided some relief by traveling along flat level ground for an hour. Beyond the lake (which we both could not even tell was a lake since it looked like a snow-covered field) we made the error of dropping too steeply into the canyon. Janet wiped out in a soft patch of snow landing on her face and jamming her sunglasses into her forehead. I heard her yell out and turned and went over to her. Blood was covering her forehead. A large rug burn type gash covered a large part of her head! She spent a few minutes stopping the bleeding with a tissue. We both drank water and had a bite of food. I think at this point we realized there was no way in hell we were going to get out before the sun went down.

In a small opening in the ridge, I turned on my walkie-talkie radio and was surprised to reach Janet's daughter who was at the car at our exit point. This was good, because had we not been able to tell her our situation she may have been worried for our safety. I assured her we were tired but ok, would make camp and try and call again in the morning when we departed. We headed back towards the lake and agreed that we severely needed more drinking water. We spent an hour going back up the canyon across the flats to a small area where Hellroaring creek snakes its way through the snow-covered field. Since the snow was too high along the edge, we could not reach down to fill our water containers. I devised a plan to unfold my avalanche probe pole which is 10-feet long and hook my water bottle on the end of the probe. I could then use this to lower the bottle to the water and scoop out water and refill all our water containers. We were both somewhat dehydrated at this point and each drank nearly a quart of water each. We didn't have a water filter with us and agreed that we didn't care. We thus drank directly from the upper source of the longest water system in North America!

Once hydrated we headed back across the open field toward the lake. Janet suggested the large group of trees on the upper end of the lake as a place to spend the night. We didn't carry a tent or heavy sleeping bags. We knew it would be a very uncomfortable cold night with very little sleep if any. The only thing that made us a little uncomfortable was the fact that neither of us had any matches or a lighter to start a fire! What the FUCK were we thinking! In the years of back country skiing and hiking I've always had fire starter. Not this time. Something got lax along the way, I got lazy in believing we would be out in 6-hours!!!! WRONG!!!! This was a good realty checkpoint for both of us, sort of a wakeup call to pay attention to "the moment", realizing the map was NOT the territory. We could have been in worse shape. We both had extra clothing and hats to wear, I carried a small bivy sack I could climb into for extra warmth. Janet's entire feet and lower half of her legs would slide into fit entirely into her backpack.

I attempted to make a fire using the lens from my binoculars and focusing the sun's beam onto some paper and sticks. No luck! A shelter was quickly constructed. Janet used her shovel to dig an area out of the snow like two side by side recliner chairs. I placed our probe poles and ski poles over the top to create the framework for a roof. I then gathered pine tree limbs and bows and covered the sides, top and bottom of our shelter to help protect us from the cold.

Prior to departing that morning, Janet's daughter gave me a 24-oz. can of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer as sort of a "victory at the source" beverage. We were determined we needed the fluid, and the 240 calories of carbohydrates it provided. And I sure as hell was not going to carry it out the next day. So once we finished with our shelter, I popped open the can and we passed it around until it was gone. Probably not the best beer I've ever had since the air temps were already dropping into the teens and the beer too was almost too cold to drink.

Since I or we (no blame here...we are all responsible for ourselves...we just made a few errors in judgement with our time) had eaten what food we had during the day we went to sleep deprived of a big meal. I in fact ended the evening with my final item of food for the entire trip .... a Hershey chocolate bar!

Janet nor I were concerned or worried about any danger in all reality. In fact, we were in great sprints-- having just rehydrated on a lot of water, built a shelter, talked to Haley on the radio, drank a beer, put on all our warmer cloths, ate a bite of food, and not having to ski no more for the rest of the day! We figured the temps would drop into the teens. Not a cloud in the sky as the sun disappeared in the west.... the twilight blue of the snow darkened only slightly....by 9pm the giant moon popped over the ridge shining down onto our home for the night. The moons light was so bright that we could see miles back up canyon.

With all our cloths on we tossed and rolled around all night. Janet was probably the coldest however I didn't know this until the next morning when she told me how cold she had gotten. We passed the entire night without speaking, only concentrating on our discomforts. I actually drifted off to sleep maybe 10-minutes the entire night. Still wearing my heavy large ski boots I tried to wiggle my body into the pine boughs and sides of snow shelter...nothing was comfortable. I could hear Janet every few minutes trying to reposition herself with her own discomfort. The moon arced across the sky all night and by around 6am the faint light of a new day was starting to form.

We most likely would have gotten several hours of sleep had we had a fire. Upon awaking, Janet exclaimed "that was the worst night of my life!"...I think I second that! We packed our gear in near silence, trying to warm up and fully awaken from miserable night. We departed our shelter about 730am....we had only about 4 1/2 miles to go! Little did we know that it would take another 8 1/2 hours to reach the end.

We began our climb up into the trees gaining a high point on the ridge. We both could see the rock canyon at the exit of Hellroaring Creek...yet hours away. An hour or so later we found the small wooden sign marking the CDT-Continental Divide Trail which goes from Mexico to Canada! We celebrated this small confidence and moral booster. We tried to follow the trail but since the ground is snow covered, it was impossible. Again, we dropped too low and had to climb back up. Constantly losing elevation only having to climb back up which we painstakingly had just descended.

I was having challenges dealing with the demons in my mind telling me we would not make it out of here for another night. I was determined to beat this devil away and not become the subject of another John Krakauer book about ill-prepared wilderness travelers dying in the back country.

Our exhausting and frustrations would occasionally well up to the surface between us and pour out as outburst, a few terse words or sighs of disbelief in having to climb back up 300-feet where we already were. We both knew we could not spend another night out in the cold.

We both commented on the descriptions of past travelers and how their journey was nothing like what we were experiencing. Even the description of people who ski this area regularly seemed far from reality.

Probably the best decision we made on this day was to take off our skis and walk in our boots! We attached the skis to the outside of our packs and walked through the snow. This allowed for quicker travel since we no longer had to work our long skis through the tight and confined forest trees. We were able to walk more in a straight line. Since the nights had been cold the snow stayed firm. We rarely broke through more than an inch or two until later in the day when the snow softened a little more. We could see the "knob" at the end which we had to skirt around getting closer and closer. Occasionally we would see old ski tracks in the woods and would follow them until they disappeared. This boosted our confidence knowing that other people had been coming in this far for a day of skiing. We dropped to the level of the creek. It was wide and open in some areas, whereas other areas the sides dropped too steeply into the creek. Along the bottom I noticed a set of grizzly bear tracks. They looked a few days old but provided something else to be aware of. We were both carrying bear-spray...which is a pressurized canister of capsaicin-- sort of like a mini fire extinguisher. Capsaicin is made from chili peppers and when sprayed at a bear it causes temporary blindness and respiratory trauma. There has never been a human casualty from a grizzly bear attack from using bear spray!

I knew we had the potential to encounter a bear since it is spring and they have been coming out of hibernation now for a month. Later we saw a fresher set of tracks probably a day old. We began to make more noise as to spook the bear. Grizzly have a fear of man too and they prefer not to be anywhere near a human. Most all bear attacks are from people who are too quiet and end up surprising a mother bear and her cubs. Thus I hollered, whistled, and made loud noises as we proceeded though the woods. The closer to the outlet of the canyon our adrenaline was high. We were certain we would be out soon. I occasionally was able to reach Janet's daughter on the radio. The conversation was broken by the weak signal but I was able to say we are making "progress".

We soon had dropped enough in elevation that we encountered patches of dirt and open rocky scree fields which we traversed. Near the canyon bottom we tried to find the so-called bridge but it must have been under 5 feet of snow still. Exhausted, hungry and mentally drained we stopped to rest and drink more of the river water we collected the day before. The sun was shinning bright, temperatures were probably in the high 50's, and the snow was getting soft and mushy. The crux of our journey would be one final 400 ft. climb up thought a notch to the left of the canyon. Slow and steady.....one foot in front of the other. We picked a route that was more open so as the skis on our packs would not get hung up on hanging tree limbs. I was still hollering out at mama bear...as to give her a little warning as to our presence. At the very top of the notch was the freshest grizzly bear tracks we had seen. The bear was most likely there just 5-minutes before!! We could tell that the bear had heard me making noise since the tracks made a 90-degree right turn away from us at that particular point! We could see the claw marks and the perfect outline in the melting snow.

A quick 20-minute drop down through trees led us to the valley floor where we had clear contact by radio with our support crew and the vehicles!

We made it to Browers Spring and out! What we thought would take a total of about 6 hours took us 31 hours! I was impressed with Janet's determination and constant forward progress when I knew she was totally spent. There were times I knew she would cringe when I said that we had to climb back up and over another ridge. One step and time, one stroke at a time will get you to the ocean!

Go Janet Go!

Norm Miller

Livingston, Montana

April 28, 2013

Hell Roaring Creek, Red Rock Lakes, and the a portion of the Red Rock river are located within the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. There are many restrictions as to the mode of travel through the refuge due to rare bird nesting and other wildlife concerns. It is virtually impossible to descend from Brower's Spring completely by water to Lima. Due to the rules of the refuge, water levels, fences across the stream, downed and fallen trees, and low bridges, the "Source to Sea" paddler will need to portage his craft around a majority of the route. This can be done by the use of the dirt road that follows the watershed. Make sure you read as much of the information from the paddlers before you about this challenging and dangerous route. Click the Refuge Logo above for more info on that area.

In summary of the route, the source to sea paddler's goal is to travel the watershed, 3800 miles to the Gulf of Mexico. This will require you to ski, snowshoe, and or hike to the spring and beyond. You may want to hike, bike and even haul your boat along the road with you on a portage cart to your chosen put-in location. As mentioned before, there has only been 12-known persons accomplish this due to the challenges. Good luck in your endeavor!

In summary of the route, the source to sea paddler's goal is to travel the watershed, 3800 miles to the Gulf of Mexico. This will require you to ski, snowshoe, and or hike to the spring and beyond. You may want to hike, bike and even haul your boat along the road with you on a portage cart to your chosen put-in location. As mentioned before, there has only been 12-known persons accomplish this due to the challenges. Good luck in your endeavor!